Photo Source: Elizabeth Warren

Calls for Taxing the Rich Are Everywhere

Promises are mounting in the Democratic Party’s primary debates as contenders try to outbid one another on free health care, free public education, or, in the case of Andrew Yang, just free money. Senator Elizabeth Warren plans to make college free in addition to canceling student debt for millions of people at an estimated cost of $1.25 trillion over 10 years. Senator Bernie Sanders’s “Medicare For All” bill would cost $34 trillion dollars over 10 years.

This bill alone would almost double the entire US government’s expenditures. Double! Current expenses include interest on the massive national debt, planes, aircraft carriers, tanks and missiles, numerous agencies, NASA and its contributions to the International Space Station, road construction, foreign aid, etc. Sanders’s plan would essentially add a second US government on top of the existing one despite the fact that the current government already spends more than it takes in.

Pointing this out has been labeled a “Republican talking point” (as if the Republicans ever cared that much about balancing a budget). It is heartening, however, to see that journalists are willing to press Democrats on how they will actually pay for these extensive programs.

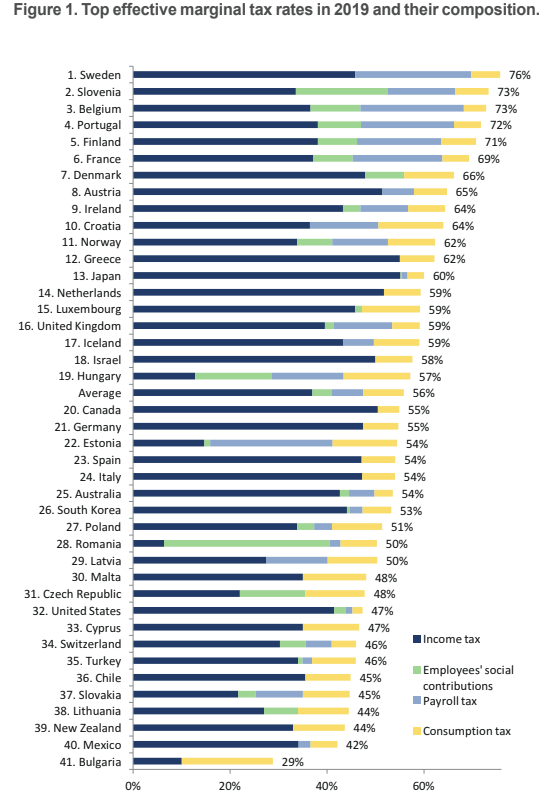

Both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren suggest taxing the rich as a solution to the revenue problem their proposals would engender. They often liken their tax ambitions of making the rich “pay their fair share” to tax rates in Europe. A new report on marginal tax rates offers some perspective on that claim.

The Real Cost of Taxation

EPICENTER, the European Policy Information Center located in Brussels, just released its “Taxing High Incomes” report, written in cooperation with the Swedish free-market think tank Timbro and the Tax Foundation, which answers the most interesting questions on marginal tax rates.

The marginal tax rate is the rate that applies to the last unit earned. In a progressive tax system, this is the rate at which the last portion of a taxpayer’s income is taxed, meaning how much you pay on every additional dollar. A distinction is made between the marginal tax rate and the marginal effective tax rate, which also takes into account the amounts paid by the state to the taxpayer (allowances, subsidies, etc.). Thus, answering the question as to how much the rich really pay in taxes is a complicated one.

This is why the EPICENTER report, comparing top effective marginal tax rates on labor income in 41 OECD (Office of Economic Cooperation and Development) and EU countries is so interesting. For instance, the report looks at social security contributions such as health care and pensions that are tied to previous income. As the authors explain, however, social insurance benefits are capped in most cases. Therefore, any social security contributions paid on high incomes can usually be regarded as pure taxes.

The report outlines how many taxes can hit high-income earners on every additional dollar. Nominally lower income tax rates do not equate to lower marginal rates. For example:

Hungary has a flat income tax of 15 percent while the United States has a progressive federal income tax with a top marginal tax rate of 37 percent. As payroll and consumption taxes are low in the United States, the effective marginal tax rate is not much higher, at 47 percent. In Hungary, on the other hand, substantial social security contributions are paid by both employers and employees. In addition, the country has the world’s highest VAT. The result is an effective tax rate of 57 percent—13 places higher than the United States in the country rankings.

The United States actually does not have low marginal tax rates, as they close in on 50 percent for the highest earners. A number of analyzed states, namely Cyprus, Switzerland, Turkey, Chile, Slovakia, Lithuania, New Zealand, Mexico, and Bulgaria all end up with lower marginal tax rates.

Is Sweden’s 76 percent tax rate the end goal of the Democratic candidates? If so, they should tread carefully. The EPICENTER report outlines the conflict between efficiency and equity in tax systems and explains how in the long run, high marginal tax rates can affect career choices and migration decisions in addition to lowering returns on education and entrepreneurship.

As capital flight (people relocating due to high tax rates) increases and interest in investment and entrepreneurship diminishes, the question remains: who will pay for the programs Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are promising?

Recent Comments