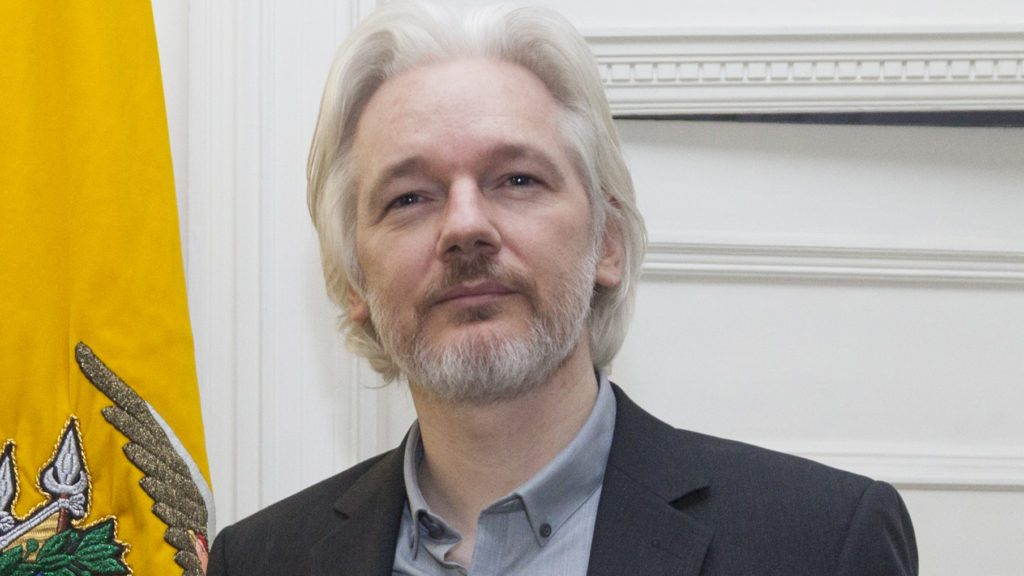

Before WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange gained asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London in 2012, he and his British legal team asked me to fly to London to provide legal advice about United States law relating to espionage and press freedom. I cannot disclose what advice I gave them, but I can say that I believed then, and still believe now, that there is no constitutional difference between WikiLeaks and the New York Times.

If the New York Times, in 1971, could lawfully publish the Pentagon Papers knowing they included classified documents stolen by Rand Corporation military analyst Daniel Ellsberg from our federal government, then indeed WikiLeaks was entitled, under the First Amendment, to publish classified material that Assange knew was stolen by former United States Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning from our federal government.

So if prosecutors were to charge Assange with espionage or any other crime for merely publishing the Manning material, this would be another Pentagon Papers case with the same likely outcome. Many people have misunderstood the actual Supreme Court ruling in 1971. It did not say that the newspapers planning to publish the Pentagon Papers could not be prosecuted if they published classified material. It only said that they could not be restrained, or stopped in advance, from publishing them. Well, they did publish, and they were not prosecuted.

The same result would probably follow if Assange were prosecuted for publishing classified material on WikiLeaks, though there is no guarantee that prosecutors might not try to distinguish the cases on the grounds that the New York Times is a more responsible outlet than WikiLeaks. But the First Amendment does not recognize degrees of responsibility. When the Constitution was written, our nation was plagued with irresponsible scandal sheets and broadsides. No one described political pamphleteers Thomas Paine or James Callender as responsible journalists of their day.

It is likely, therefore, that a prosecution of Assange for merely publishing classified material would fail. Moreover, Great Britain might be unwilling to extradite Assange for such a “political” crime. That is why prosecutors have chosen to charge him with a different crime of conspiracy to help Manning break into a federal government computer to steal classified material. Such a crime, if proven beyond a reasonable doubt, would have a far weaker claim to protection under the Constitution. The courts have indeed ruled that journalists may not break the law in an effort to obtain material whose disclosure would be protected by the First Amendment.

But the problem with the current effort is that, while it might be legally strong, it seems on the face of the indictment to be factually weak. It alleges that “Assange encouraged Manning to provide information and records” from federal government agencies, that “Manning provided Assange with part of a password,” and that “Assange requested more information.” It goes on to say that Assange was “trying to crack the password” but had “no luck so far.” Not the strongest set of facts here!

The first question is whether a legal theory based on such inchoate facts will be sufficient for an extradition request to be granted. Even if it is, a grant of extradition could be appealed through several layers of courts, which would take a long time. The second question is what would happen to Assange while these appeals proceeded. If he were locked up, he might well waive extradition in the hope of winning his case in the United States. The third question is whether American prosecutors might amend the indictment to make it legally and factually stronger and, if they did so, whether they would take such action before or after he was extradited.

The last question is whether Manning will testify against Assange. It is not clear whether prosecutors really need her testimony or whether they can make the case based on emails and other documents, but her testimony surely would be helpful if she were to corroborate or expand on the paper trail. President Obama commuted her sentence in 2017 and she was freed from prison, but she was jailed last month for refusing to testify against Assange before a grand jury. Manning could be given immunity from further prosecution and compelled to testify. But if she refused, would prosecutors keep her in prison? There are lots of moving parts to this process, all of which make its outcome and timetable unpredictable.

via The Hill

Recent Comments