In the spring of 431 b.c., Athens and Sparta went to war. Their dispute soon enveloped the entire Greek world. Thucydides, an eyewitness to the fighting, wrote that it would be “more momentous than any previous conflict.” He was right. Dragging on for 27 years, the Peloponnesian War anticipated the suffering and deprivation associated with modern conflicts: the atrocities, refugees, disease, starvation, and slaughter. The war destroyed what remained of Greek democracy and left the Greek city-states vulnerable to demagogues and foreign invasion.

A hundred years ago, on November 11, 1918, another war begun by two European states—a local squabble that escalated into global conflict—came to an end. Struggling to describe its scope and destructive power, the combatants called it the Great War. Like its Greek counterpart, the war ravaged soldiers and civilians. Over the course of four years, roughly 20 million people were killed, another 21 million wounded. National economies were ruined; empires collapsed. The war to “make the world safe for democracy” left European democracy in tatters.

And more than that: The core commitments of Western civilization—to reason, truth, virtue, and freedom—were thrown into doubt. T. S. Eliot saw the postwar world as a wasteland of human weariness. “I think we are in rats’ alley,” he wrote, “where the dead men lost their bones.” Many rejected faith in God and embraced materialistic alternatives: communism, fascism, totalitarianism, scientism, and eugenics.

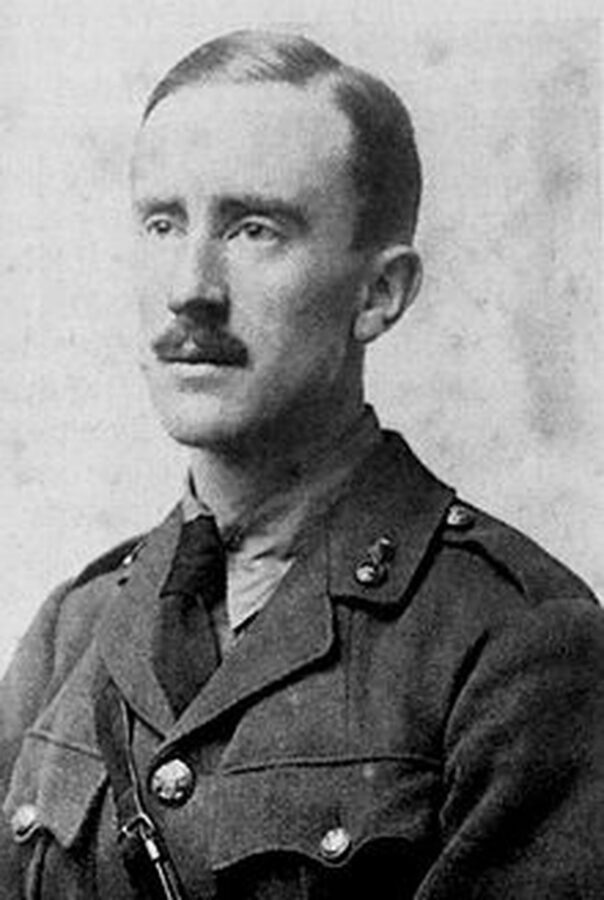

Yet two extraordinary authors—soldiers who survived the horror of the trenches—rebelled against the spirit of the age. J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, who met at Oxford in 1926 and formed a lifelong friendship, both used the experience of war to shape their Christian imaginations. In works such as The Lord of the Rings, The Space Trilogy, and The Chronicles of Narnia, Tolkien and Lewis rejected the substitute religions of their day and assailed utopian schemes to perfect humanity. Like no other authors of their age, they used the language of myth to restore the concept of the epic hero who battles against the forces of darkness and the will to power.

One of the most striking effects of the war was an acute anxiety, especially in educated circles, that something was profoundly wrong with the rootstock of Western society: a “sickness in the racial body.” Book titles of the 1920s and ’30s tell the story: Social Decay and Regeneration (1921); The Decay of Capitalist Civilization (1923); The Twilight of the White Races (1926); The Need for Eugenic Reform (1926); Will Civilization Crash? (1927); Darwinism and What It Implies (1928); The Sterilization of the Unfit (1929); and The Problem of Decadence (1931).

The promotion of eugenics—from the Greek for “good birth”—began in Great Britain in the years leading up to World War I. But it gained international support in the period between the two world wars, just as Tolkien and Lewis were establishing their academic careers. The aim of the movement was to use the tools of science and public policy to improve the human gene pool: through immigration restriction, marriage laws, birth control, and sterilization. The movement’s first task was to educate and persuade a potentially skeptical public. Sir Francis Galton, the British sociologist and cousin of Charles Darwin who coined the term, explained that eugenics

…must be introduced into the national conscience, like a new religion. It has, indeed, strong claims to become an orthodox religious tenet of the future, for eugenics co-operate with the workings of nature by securing that humanity shall be represented by the fittest races. What nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly, man may do providently, quickly, and kindly.

The success of the movement was breathtaking. In The Twilight Years: The Paradox of Britain Between the Wars, historian Richard Overy writes that eugenics advocates soon represented mainstream science, becoming affiliated with leading academic and scientific organizations on both sides of the Atlantic. “The concept appealed,” he writes, “because it gave to the popular malaise a clear scientific foundation.” At an international eugenics conference in Paris in 1926, Ronald Fisher, later a leading Cambridge geneticist, suggested that the new science would “solve the problem of decay of civilizations.” Two years later, at University College London, Charles Bond argued that biological factors were “the chief source of the decline of past civilizations and of earlier races.” At the 1932 Congress of Eugenics in New York, an international cast of geneticists, biologists, and doctors were assured that eugenics would become “the most important influence in human advancement.”

The perspective of these two Oxford friends is remarkable when we consider another of the pernicious effects of the First World War: the widespread erosion of the concept of individual freedom and moral responsibility. Literary critic Roger Sale has called the war “the single event most responsible for shaping the modern idea that heroism is dead.”

Consider what the soldiers at the Western Front were made to endure. The mortars, machine guns, tanks, poison gas, flamethrowers, barbed wire, and trench warfare: never before had technology and science so catastrophically conspired to obliterate man and nature. On average, more than 6,000 men were killed every day of the war. Their mutilated remains were consigned to graves scattered across Europe. The helpless individual soldier chewed up in the hellish machinery of modern warfare became a recurring motif of the postwar literature. In his All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), Erich Maria Remarque described a generation of war veterans “broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope.”

But the purveyors of fatalism found in Tolkien and Lewis implacable opponents. In the worlds they created, everyone has a role to play in the epic contest between Light and Darkness. No matter how desperate the circumstances, their characters are challenged to resist evil and choose the good. “Such is oft the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world,” wrote Tolkien. “Small hands do them because they must, while the eyes of the great are elsewhere.”

As soldiers of the Great War, Tolkien and Lewis endured the most dehumanizing conditions ever experienced in a European conflict. Their generation then watched with dread as totalitarian ideologies threatened to dissolve the weakened moral norms of their civilization. Others, such as Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, raised the alarm but seemed pessimistic about the outcome. A New York Times review of That Hideous Strength discerned in Lewis a different spirit: “When Mr. Huxley wrote his bitter books his mood was one of cynical despair. Mr. Lewis, on the contrary, sounds a militant call to battle.”

Tolkien and Lewis possessed two great resources that helped them to overcome the cynicism of their age. The first was their deep attachment to the literary tradition of the epic hero, from Virgil’s Aeneid to Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. What matters supremely in these works is remaining faithful to the noble quest, regardless of the costs or the likelihood of victory. “The tragedy of the great temporal defeat remains for a while poignant, but ceases to be finally important,” Tolkien explained in his 1936 British Academy lecture on Beowulf. In the end, “the real battle is between the soul and its adversaries.”

The second great resource was their Christian faith: a view of the world that is both tragic and hopeful. War is a sign of the ruin and wreckage of human nature, they believed, but it can point the way to a life transformed by grace. For divine love can reverse human catastrophe. In the works of both authors we find the deepest source of hope for the human story: the return of the king. In Middle-earth that king is Aragorn, who brings “strength and healing” in his hands, “unto the ending of the world.” In Narnia, it is Aslan the Great Lion, who sacrifices his own life to restore “the long-lost days of freedom.” In both we encounter the promise of a rescuer who will make everything sad come untrue.

As the world marks the centennial of the end of the Great War and remembers the many lives swallowed up in its long shadow, here is a vision of human life worth recalling, too.

Dustin Koellhoffer

This is an outstanding article! I’m sharing it on my blog. Lewis and Tolkien held true to the Christian spirit. Their great heroes, like Aragorn were supplemented by unlikely great heroes like Samwise Gamgee without whom the quest to destroy the ring would have failed. Aslan and Gandalf are their Christ figures guiding them in righteousness. I cannot help but think of the rare great words that come in comics and hero movies that better fit than the words of Alfred Pennyworth when he lay dying. “There is no defeat in death, Master Bruce. Victory comes in defending what we know is right while we still live.”